Testing Pt.2: Experience

What follows is an athletes experience of the testing protocol as explained in the previous post Testing Pt.1: Protocol.

The evening before is filled with trepidation, as it is before any kind of test. Tomorrow is going to determine whether I have a future in this sport.

Wait; no, it won’t. It’s going to tell me how I can get better. It’s going to determine what my future looks like within the sport.

Thursday - Day One: Test 1

The alarm goes off at 05.30. Not uncommon, but something I’ve become less conditioned to in the current circumstances that have been dictated by coronavirus.

There’s no time for breakfast. I manage to inhale an espresso as the cranks start turning and, after a five-minute spin and coach-prescribed warm-up, my muscles twitch back into life, blissfully unaware of what they’re about to endure. Secretly, I’m hoping my drowsiness will numb the pain.

It’s time to crack on with the ramp test that’s been planned. The steps have been drawn up and I’m quietly confident that I won’t fail. In fact, semi-optimistically, I sneak on an extra minute and add an additional 25 watts.

My confidence grows as the test progresses. I actually feel pretty good. My heart rate, breathing and cadence increase with the power, along with the compounding tick that marks each revolution of the cranks.

Hitting the fifth of the eight (planned) stages, I reason with myself that it’s time to abandon the TT position; there are no races upcoming, so let’s just do whatever it takes to get the power out.

Breathing hits the red line around the 28-minute mark. Pure inhalation has ceased to work. Its teeth-gritting time. ‘Just get through these last 3 minutes’ becomes the mantra. I might be red hot, but I know I can do it. And I’m still glad I threw that extra minute in.

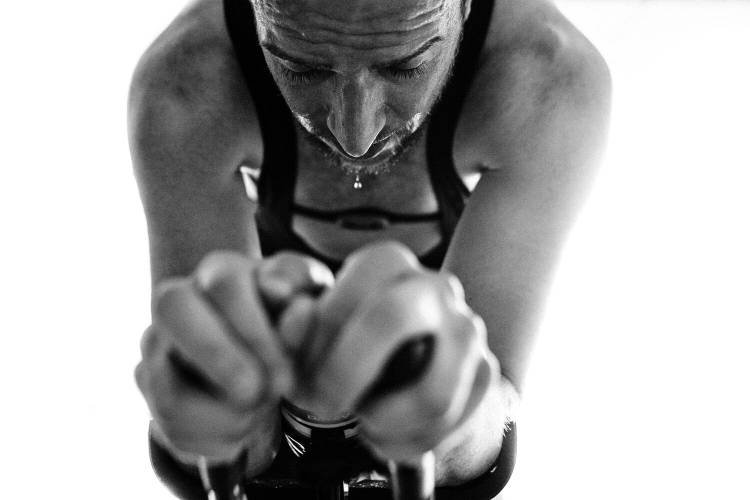

I hit the last interval in a full seated sprint for 17 long seconds before I throw in the towel (or, more accurately, I fold myself into the towel and over the handlebars).

Success? I didn’t fail, at least not the proper test.

Strictly speaking though, it’s not.

I didn’t fail, meaning my power targets were a bit low, likely because I was using an old PB. Apparently, I’ve drawn out some decent form during my lockdown efforts.

Friday - Day Two: Recovery

Recovery day consists of an easy 60-minute run and a distinct lack of what I’d normally deem necessary to recovery: a beer to reward for my efforts.

That’s two on Saturday night, then. Right?

Saturday - Day Three: Test 2

06.30 alarm. A blissful lie-in compared to Thursday. That numbing effect will be sorely missed but I’m happy to forsake it to hit a 3 minute, all-out effort, 15 minutes after starting.

Breakfast remains unchanged: a quick espresso, although today it’s served with a few extra moments to savour it.

07.00 and I’m rolling once more. The planned workout has been programmed into Zwift, utilising the free ride option for the efforts. No ERG mode and no gradient resistance, just the basic maths of cadence x torque.

After a few short, sharp efforts, I wind down in preparation, holding the higher-than-normal cadence that this effort is going to require. Straight out of the gates, I launch into an all-out effort.

3 minutes

There really is no hard and fast pacing strategy other than to go really hard and really fast.

I’ve been given a power range to target, but I figure I’ll hit the first minute and reassess. I fly through it with 445 watts, up on the target, and an average cadence of 98. My heart rate climbs to 170bpm.

I’m feeling good. Thirty seconds on and I’m halfway there except now I feel different. Every sense is heightened and I begin frantically observing anything and everything to pass the time. I’m trying to bring objects in my periphery sharply into focus. The clock, the garden, the clock, the cawing magpie, the clock, literally anything, the clock.

It’s been ten seconds.

There’s no satisfaction in looking at the power display. The numbers are intangible. Whatever they say, if I could do anything to improve them, I would.

Final 30 seconds. A marginal resurgence allows for a slight rise in cadence before I’m done.

435 watts for 3 minutes. A little over 6w/kg.

It’s nothing spectacular but it’s a reasonable result for someone who’s by no means a pursuiter. The slight drop in power across the last two minutes would likely raise the eyebrows of a perfectionist, and they’d probably tell me I could have hit 440 watts in total, but that would change next to nothing in the grand scheme of things.

Thirty minutes of easy spinning starts to erase the memory of the previous effort. It’s soon repressed even further once I begin warming up for the final twelve minutes.

The three-minute test exuded a fear of the unknown – a level of power I’m not accustomed to as a middle-distance triathlete – but the twelve-minute test brings fear of failure in a different guise. Go too hard and it’s a long walk home, go too easy and the data will be inaccurate, irrelevant and the effort will be wasted.

12 minutes

Once again, I have a power range to target. My plan of attack is to sit here for 6 minutes and then crack on.

Those 6 minutes pass comfortably and I slowly start to push on. Despite being relatively comfortable, I find myself restricted by the fine margins I’ve become conditioned to. I’m happiest at 84-85rpm but I’m stuck at 83. If I drop down a gear I’d be spinning for my life just to maintain, go up a gear and I’ll be forced to grind. I’m not sure my legs can sustain the high torque this late into the stage.

Now I find myself trying to reason with my conscience (and my legs); ‘hold on until eight minutes, then go all in’.

8 minutes arrive. I’m not sure anymore. The memories of those first 3 minutes are coming back to haunt me. There’s no way I’m putting myself through that again.

Less than 3 minutes to go. I free myself from the restraints and manage to ramp up considerably. My average is up to 345w. The final surge wasn’t exactly exemplary pacing, but it was better than falling off. I’ll take that.

Time to crunch the numbers.

The Results

The lack of recent testing and estimates actually hindered my current test. More recent results would have provided more accurate power targets, giving the perfect demonstration of why frequent testing is so necessary.

Completing a full stage at 380 watts (w), and 15 seconds at 410w provided an estimate PVO2Max of 380.

Using my 3-minute max of 435w and a 12-minute max of 345w, my critical power (CP) is calculated at 315w.

These figures in isolation were roughly where I expected them to be. It was the next tier of results that surprised me.

I’ve always been a diesel engine; the longer the race, the greater my chance of success. By comparing the critical power to my PVO2Max, my efficiency was estimated at 82-83%, a long shot from where I thought I was. As well as this, my anaerobic capacity (the amount of time I can spend over CP) was, to quote my coach, ‘one of the biggest [he’s] ever seen’.

None of this really added up. My 3-5 minute power was low compared to a lot of the guys at my level, and why was my efficiency so low? Turns out, I’m a very inefficient diesel engine.

The answer lies in my training programme, at least in part. Amongst other things, my training may be too polarised in comparison to my CP; either too far above or below. Pairing this with lengthier recovery sessions means my anaerobic system is replenished in preparation for the next repetition, so all I end up training is power at VO2max. Whilst not necessarily a bad thing – it gives me the opportunity to grow my aerobic function – it’s a good example of short-sightedness in training prescription.

Now I’m entering a 10-12 week block of specific training, designed to boost my efficiency. Whilst this block specifically targets my aerobic function, it’s likely that the overall load will maintain my PVO2Max and anaerobic capacity as well. To do this, my training programme is based on three key criteria:

Shorter Recoveries - limiting the option to recharge my anaerobic capacity thus ensuring all efforts use the aerobic system.

Longer High-Intensity Intervals - typically between 4 and 10 minutes in duration. While they’re not ‘long’ by race-specific standards, they’ll all be between 100-120% of my critical power.

Depleting Intervals - focused on ‘depleting’ my anaerobic stores with a high-intensity effort, before ‘settling’ into a longer effort at around-critical power.

I’ll check-in with a progress report midway through the training block but for now, I’ll crack open those two beers.